Milan XPUG January Meetup: My Advice on Microservices Architecture, by Gabriele Lana

Hi 👋 and welcome to a new post!

Today I want to share with you a summary on the last meetup I attended, organized by the Milan eXtreme Programming Group.

This time , Gabriele Lana gave his advice on the pros and cons of microservices, and the problems (and solutions) that he found in his experience.

Gabriele is a consultant with over 20 years of experience, founder of the Milan XPUG and a nerd at heart (he still likes to play with cabinets and has contributed to a NES simulator in emacs, among other stuff!!).

Let’s begin!

Microservices Architecture Definition

Gabriele started with a premise: Microservices are currently (and have been for years) still in their “hype” phase. Hype is a double-edged sword: it means that it’s easier to get buy-in for using them, but (as all engineers know) there’s the risk to fit the problem to the solution, instead of finding the right solution for the job. In fact, microservices are most of the times used without proper reasons, and that’s the main source of issues.

Then, he gave a simple definition of microservices (which can be used to describe anything really, as he admitted): “Microservices are small, autonomous services that work together”.

But how big should a microservices be in reality? Given the “micro” prefix, we might think that their size matters. Some schools of thought say they should be as big as a small team can implement in a month, others will talk in terms of number of lines (hundreds? thousands?). The advent of serverless computing has made thei size even more relevant.

Gabriele gave the usual answer: it depends!

But what does it depends from? For Gabriele, the size of a microservice should be intended as the size perceived from outside, such as the API surface. A microservice might have millions of lines (e.g. doing video encoding and processing) but still be “micro” because it does just one thing!! On the other hand, a small CRUD service might have a large surface area and handle a lot of entities, and thus be too complex to make a single microservice. In the end, the size depends on the domain of the system we are going to develop for.

Pros and Cons

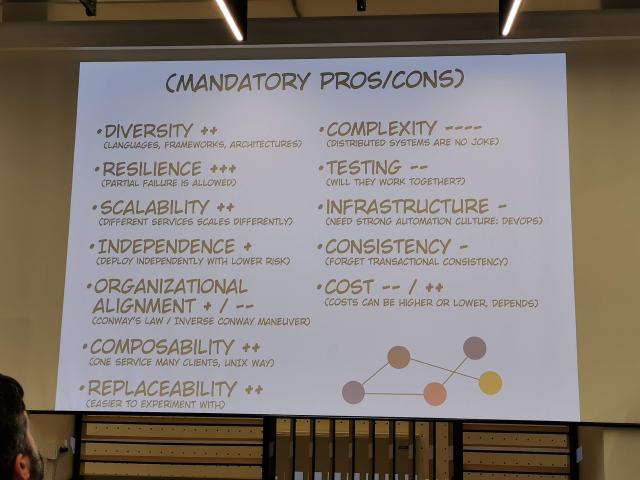

After giving a mandatory definition of microservices and their “micro”-ness, Gabriele gave an overview of the pros and cons of employing a microservices architecture in our systems.

Pros

Let’s start with the pros of microservice architectures:

Diversity

With microservices, the company can diversify their technology: each microservice can in fact be implemented with the most suitable language or framework for the problem. In addition to this, diversity allows to integrate new technologies in a system without rewriting everything from scratch! It also allows to be more appealing to engineers who want to learn new languages, and to follow the trends (still being cautious of using too much new technology - stick to the old, good stuff!). One con of diversity is that it can bring more complexity (see below) and requires more standards and a better culture.

Resiliency

If you partition well the responsibilities inside the system, splitting it in multiple microservices helps increase its availability. Even when some services are down, the others stays up, and that increases the resiliency of the application as a whole.

Scalability

By splitting an architecture in services, each functionality can scale differently from the others. For example, a central feature of the system might need more resources to run and be used by many users, while other parts of the system might need less resources. This scalability pro is even more useful when using serverless architectures, which in some cases can help cut costs considerably.

Independence

Independence here is related to the possibility to independently deploy different parts of the system at different times and frequency. By deploying services independently, we can keep the availability of the system high and allow developers to develop features without the fear of “big bad deployments” (the one you don’t want to do on a friday).

Organizational Alignment

Conway’s law states that

Organizations which design systems are constrained to produce designs which are copies of the communication structures of these organizations.

Following this law, using microservices helps in aligning the technical side of the system to the topology of the organization (e.g. assigning a microservice to each team separately).

However, microservices can also lead the opposite to happen, called Inverse conway’s law: given an existing system, the organization is forced to organise in the same way as the system’s components! This is usually difficult to perform, and leads to issues down the line.

Composability

Here Gabriele just said “ah…classic” 🥲 so I have nothing to write.

If I have to add two lines on the argument, I can cite something Gabriele said later, which is that microservices are just a deployment method, and all the rest is standard software architecture and design. So, composability is not a pro by itself, but it’s a requirement for doing microservices 😜.

Replaceability

Finally, microservices are easily replaceable. I can implement a service, then experiment with it. The usual examples are canaries (used in deployments) and A/B tests. By being independent and resilient, microservices allows to experiment much more than a monolith, without impacting on the entire product at once.

Cons

After listing all the (somewhat) pros of microservices, Gabriele started explaining the cons. They are less than the pros, but of way higher magnitude, and can impact much more the business and the developers if encountered.

Complexity

Microservices introduce complexity on multiple levels. The main one is the communication. Calling a method in a monolith is a straightforward thing to do: just call the method and, if no cosmic rays are involved, you will know the answer right away.

Distributed systems are a different thing altogether. When you send a message to another component, you cannot know if you will receive a response, and cannot know why (did the other component receive the message but didn’t complete? did it complete the request but I wasn’t able to receive the response? is the other component malicious?).

In addition to the inherent complexity of the network, splitting a system into multiple services introduces complexity in the communication patterns (I need other services to other data) which can be worsened if the system isn’t partitioned properly.

Testing

Microservices can make unit testing easy and fast (the service is small afterall). It’s the integration testing which becomes more difficult.

How can we test microservices?

Some techniques (such as using mocks and contract testing to check the connection with other services) are useful, but they allow to test a part of the system. Testing the whole system becomes more difficult, and testing it while maintaining independence of development and deployment is even more complex.

Infrastructure

Deploying a microservices architecture requires more automation on the infrastructure, and more so if the number of services increases. The business must have a strong DevOps culture to manage this kind of system effectively.

Consistency

Forget strong consistency and ACID properties! With microservices comes the burden of eventual consistency and asynchronous communication (at least to make the most out of it).

Cost

This is not a con per se, but a factor that must be considered. For simple application a microservices architecture might be too expensive, while it could bring the costs down for a complex system (more so if using serverless).

(Plus) Debugging

In the same way testing is more complex, debugging also becomes more difficult while dealing with microservices, especially if an issue is caused by multiple services. It’s essential to setup observability (tracing and logging) as first thing when using microservices, and even with these tools tracking an error can be difficult.

3 of the Worst Problems

The first part of this summary covers just 30 minutes of the talk. What is the rest of the meetup about (one hour and half)?

In the main part of his talk, Gabriele highlighted the 3 worst issues affecting microservices architectures, their causes, symptoms, cure and prevention!

I didn’t take much notes on this part, so this summary will be shorter than the pros/cons. To learn more, you can watch the video.

1. Wrong Responsability

The first (and worst) risk with microservices architecture is to partition the system wrong!

If you design the system the wrong way, using microservices will only worsen the issue.

Gabriele sees microservices only as a deploy model, in the sense that they aren’t a solution to bad software design, but just a tool.

When the system is badly designed (with high coupling and low cohesion) making changes becomes exponentially more difficult. When a component needs some data which is not in the right spot, it needs to communicate with another service to get it. If this happens too many times, it means the component suffers of a pattern called feature envy. The envious component keeps asking for data (or actions) to the other component.

The issue is made worse by the network: when a component is envious in a monolith, all is solved with a method call. In a microservice architecture this involves the network instead, with all its related issues (latency, availability, byzantine faults and so on)!

In the 90s/2000s vendors tried to sell similar stuff, with CORBA and RMI. This didn’t end well…instead, it’s important to reduce the communication to a minimum and employ the Single Responsibility Principle, in the same way we employ it in a standard OOP monolith. As already said above, a bad system design will just get worse with microservices.

What can we do if we have a big ball of mud monolith and need to split it? The first thing is to refactor the monolith in order to fix the mess, and only then to split it in microservices! It’s important to disentangle and uncouple all the components while it’s still easy.

“And what if everything is strongly connected because of our domain?” Gabriele provoked us with a questioner a customer may give. The solution is simple….keep the monolith! Using microservices is not mandatory, and should be done only if there is the need (and the skill) to do it. Splitting a strongly coupled system wrong instead would only lead to pain.

2. Shared Database

This is an issue I’ve been guilty multiple times: using a shared database between microservices!

First rule of microservices: each microservice must have a separate database.

If multiple services share the same db (access and schema altogether), then the database becomes the same as a central, global variable that everyone has access to. With a central database there is no independent deploy (how can I run migration and change the schema if others depend on it?) and making changes becomes difficult.

But what causes the presence of a shared database? Gabriele gave a few culprits:

- When the DB is used to configure/customise the system

- Data Driven Design (when we first design the tables and then the rest)

- Database Normalization (how we are tipically taught to design a DB schema…)

- False need of strong consistency from the business side

- Database containing business logic as the central part of the system (e.g. using triggers and stored procedures)

How can we prevent this from happening? The first thing to do it to not fear denormalization and to stop doing data-driven design. Instead, we should base our design on the behaviour and actions of the users (so DDD, BDD and so on) and learn that it’s ok to split the data related to an entity among multiple databases!

Gabriele gave the example of the humble Order entity. An order can be represented differently by each distinct department inside the company. Each can add tens of fields into it… Sometimes the order might even be created before the user is logged or even if the goods are not available yet!

What should we do in this case? Create a single table with hundreds of (mostly unrelated) fields and used by all services? Nope!

Instead, we should have a shared id for the same entity, but store it in every microservice only with the data pertaining to that service, of which the service is responsible. It might be the Shipping Address for the logistics service, the credit card details for the Finance service, and the id and position of the goods for the warehouse service.

3. Distributed Monolith

The last issue Gabriele mentioned is the infamous “Distributed Monolith”. It happens when we use too much synchronous communication when building our microservices, coupling the system and making it harder to change and deploy independently.

Synchronous communication creates more coupling than asynchronous, because when sending a synchronous request, we wait for the response…. what could go wrong? As already seen with the other 2 issues, everything!!

The solution for this issue is to embrace asynchronous communication between services (not caring if the response arrives and when) and eventual consistency. Many system can work just fine with eventual consistency, even if we don’t realise it.

Gabriele also mentioned some concepts of distributed system design that can help create a reliable distributed system, such as the use of circuit breakers. In the end, we must understand the distributed nature of microservice and not to go against it.

Conclusions

Gabriele’s talk was a long and detailed list of reasons why not to use microservices 😂. I really liked his style of presentation (without filters and talking about real systems and issues).

I recently read the book “Building Microservices” by Sam Newman, and most of the advice given in the book resonated with Gabriele’s talk, most of all in the issues that microservices can cause if not implemented properly. This discussion also remembered me that microservices are a tool, and that it all start with a good software design first (and second, third, fourth and so on 😅).

Be it an existing system or a greenfield project, it’s important to decouple and separate the system properly before splitting it, and focusing on distributed systems’ issues and solutions (such as denormalization, async communication, event-based systems and so on) can make the difference.

That’s it for this time! I hope you liked my short summary of a long talk. You can find the meetup video here.

See you next time!